How Different is European and North American Hockey?

A study into five key differences between North American, European and Professional-Level Hockey Prospects

Hockey IQ contributor Will Scouch hand-tracks event data on player performance around the world in his scouting work to prepare for the annual NHL Draft. The goal is simple: Help check what he is seeing and create a database of useful information to pinpoint the positives and negatives of a player as they are.

As we all know… context is important. An intriguing topic that has arisen is the actual differences between levels of play in the pre-NHL draft age group. It’s important to know how different leagues (or even teams) vary so they can be contextualized when analyzing players.

With well over 700 individuals tracked over the last five seasons, it feels possible to have a bird’s-eye look at the landscape and see if there’s anything we can pick out from the noise. I’ve split my tracked players into three groups:

European juniors

North American juniors

Professional prospects.

These groups showcase differences that can be contextualized. The idea is to pick out any on-ice shifts in the style of play that could be explored or understood further at a high level.

Overall shot differentials at the professional level are worse.

The key takeaway here is that players who drive good results at the pro level should be coveted, especially defensemen.

European and North American junior prospects on average control over 50% of the shot attempts while on the ice. At the professional level, they control shot attempts at a rate that is ~5-10% lower than their junior counterparts. Filtering out low-danger shot attempts, the difference remains essentially the same.

The increased speed and physicality of professional leagues are apparent and may explain this. Events happen quicker, the opponents are better, and the tactics are often more quality-driven compared to lower-end players who are shooting pucks on the net from the perimeter in high volumes. This trend affects both forwards and defensemen.

A notable example is Lucas Raymond in his SHL season before being drafted. An outstanding defense-first player who had signs of strong offensive potential, Raymond kept up with play extremely well, was often involved in the game, and drove excellent results in every area of the ice.

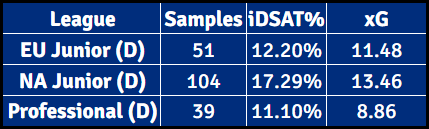

SAT% indicates shot attempt share, essentially Corsi%. DSAT% is the same, filtering out low-danger shots at both ends.

Shots come from less dangerous areas in Europe… Sort of.

One of the most common refrains we hear about in hockey is how the European game is less inside-driven than the North American game. The numbers show a level of truth to it:

53% of a professional European forward’s shot attempts come from inside scoring areas

Nearly 60% of North American junior players

57% for European juniors

European junior hockey is close to their North American counterparts regarding forwards getting to dirtier, better areas for shot attempts.

There is a difference when looking at defensemen compared to forwards.

European professional defensemen are getting pucks on net from scoring areas just 10% of the time on average

North American juniors are ahead at 17%

European juniors are sitting at ~13%.

This is noticeable as NHL prospects tend to be pushing into the professional ranks and seeking to establish themselves at that level. Hockey seems to change for defensemen once they get to professional ranks, being relied upon to defend significantly more than having the freedom to pinch into the offensive zone.

There’s a better correlation between offensive play and overall impact on the game than defensive play leading to positive overall impact. This may be an area that more players could explore more often in a responsible offensive system, but there is clearly a reason why this trend exists from a coaching perspective.

iDSAT% is the share of a player’s shot attempts from scoring areas. xG indicates the total amount of expected goals over heavy NHL equivalent usage (1900 mins)

North American players are much more inside-driven offensively.

Players at all positions in North America are definitively more driven towards getting pucks into scoring areas more often than many Europeans, despite comparable completion rates. This trend builds off of the previous point as the trend holds true when looking at playmaking, not just shooting.

“Offensive Threat” is the sum of a player’s slot pass attempts and individual shot attempts from medium or high-danger space.

North Americans are trying to thread pucks into the slot almost 30% more often than their European counterparts at the junior level, and over 60% more often than professional players. The same is true for both forwards and defenders.

The physicality, reliance on defensive safety, and the speed at which the game is played can often limit a player’s time to read the ice, get the puck into threatening space, and try to make a play.

As a share of a player’s total pass attempts, North American forwards once again lead the pack with 17% of their attempts being directed at the slot relative to Europe’s 14%, but Europeans complete these passes over 10% more often than North Americans, likely stemming from bigger ice creating bigger lanes, but this is difficult to prove.

OffThreat indicates dangerous pass attempts plus dangerous shot attempts. DPassAtt indicates slot pass attempts, DPass% is the percentage of all of their passes directed at the slot, and DPassC% indicates the completion rate of those passes.

North Americans pass the puck more but complete slightly fewer passes.

To add to #3, there are some more interesting differences to keep in mind between these broad groups.

In North America, players pass the puck slightly more often than Europeans. When it comes to actually completing passes, there are larger differences. North Americans pass more and miss more than Europeans.

Part of this may come down to North America attempting more dangerous passes than Europeans, and Europeans being on bigger ice which gives them more freedom to carry pucks and spot passes.

The difference in completion percentages is largest with professional players, which makes sense considering the heavier defensive lean in the game.

PassAtt indicates total pass attempts per 60 minutes, PassC% indicates the completion rate of all their attempts, and DPassC% indicates the completion rate for attempted slot passes.

Neutral Zone Involvement Differences

The game of hockey is often won and lost in the neutral zone. It’s a pivotal area to analyze as you can’t generate offense if you can’t get the puck into the offensive zone, and you can’t get scored on if you prevent the puck from getting into your defensive zone. Understanding the ups and downs of a player in this area could be a make or break for future success.

Maximizing efficiency offensively is pivotal to consistently generating offense. On defense, shutting down defensive transitions is about the only defensive metric that correlates to better overall shot impacts.

In my tracked data, the differences between leagues regarding offensive transitions are negligible. If you’re good, you’re good, even at the professional level, so we have fewer excuses for Europeans at that level if they seem deficient. They’re just as involved, just as successful, and essentially just as balanced between carries, passes, and receptions moving up the ice.

For defensemen, the same is true on the defensive side of the puck. Professional-level defenders are slightly more involved in defensive transitions, with comparable average results, which checks out considering the offensive limitations there appear to be in their games. If they aren’t pinching for offense as much, they’re hopefully defending the bluelines more often.

For forwards, there is an interesting trend of North Americans being less involved in defensive transitions by a solid margin, but being slightly more successful doing so. They’re essentially picking their spots better, but are either putting more responsibility on defenders or are more passive positionally off the puck, or a combination of the two.

Current information indicates slightly higher rates of physical play and a bit more success on their more limited stick-checking attempts, but this needs to be explored further in the coming years.

OTINV% indicates involvement in all offensive transitions, OTS% is the total success rate of those transitions, DTINV% and DTS% is the same, but for defensemen. Note: A low DTS% indicates more successful shutdowns of defensive transitions.

The point of this reflective exercise is to understand the context in which we evaluate players and how we can carry this information into the future.

It’s clear that players who perform well at the professional levels of hockey are desirable and often go undervalued in the NHL Draft. Even players who may not drive results as well may be framed more positively, understanding that expectations may need to be lower at those levels.

In terms of judging European juniors relative to North Americans, the overall differences aren’t huge and are a far cry from the differences that can be gathered between teams in the same league that need to be factored into a player’s analysis.

Judging a player simply because of geographic location seems like a mistake. However, understanding the general tangible differences and trends should help cut through the muck and isolate the best of the best, regardless of where they play.

Further Reading